What happens to EV batteries when they are no longer needed?

Words by Vicky Parrott

Electric cars aren’t the future any more, they’re here and a part of our transport system today. At the end of July 2020, there were over 136,600 pure electric cars on UK roads, and 330,800 plug-in hybrids. Globally, it won’t be long before there are millions of electric cars out there. Nissan has already produced half a million Leafs, and Volkswagen alone expects to have produced one million electric cars by 2025.

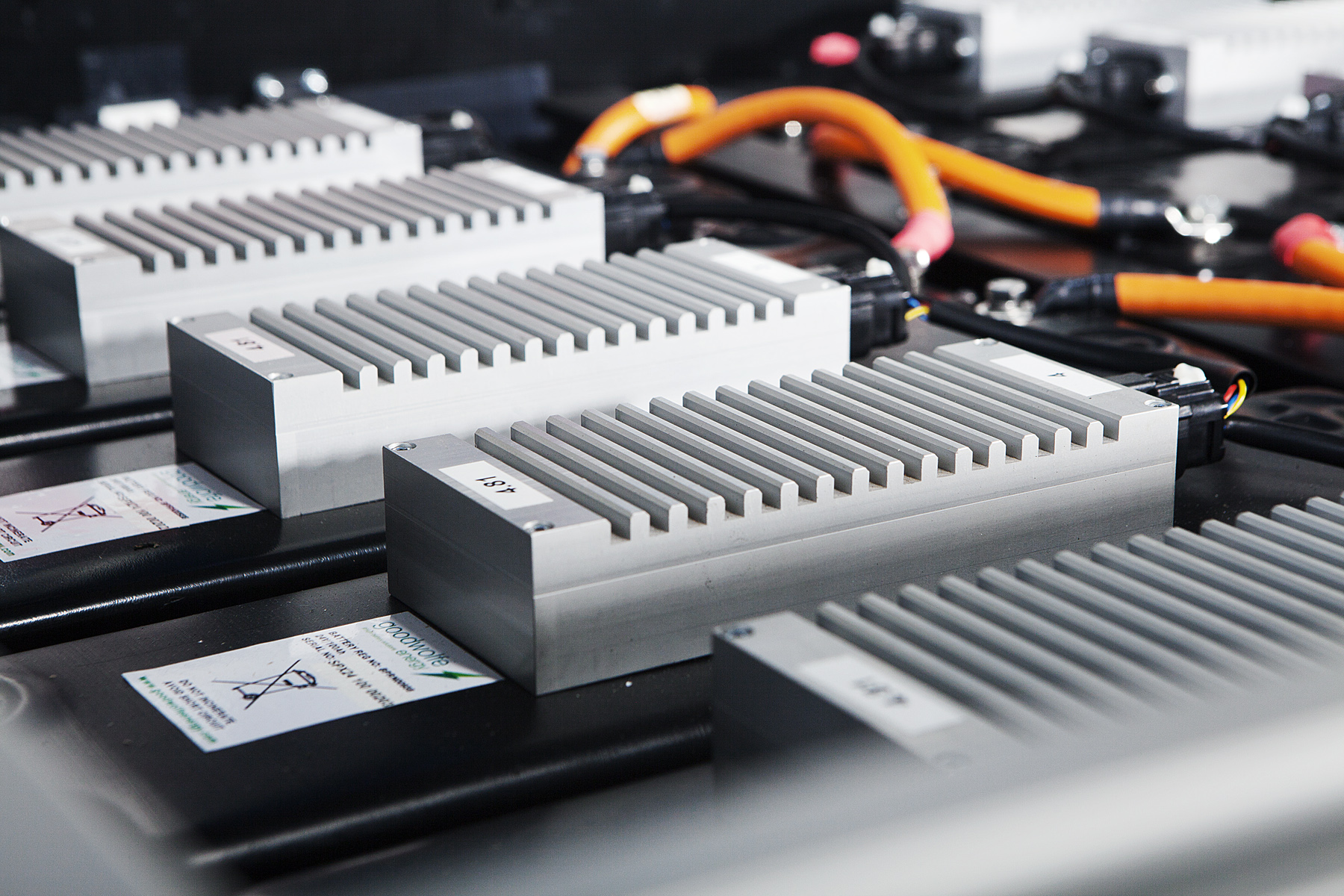

This seems an environmental win, no doubt, but there is an often-overlooked ecological burden associated with them: the batteries.

Modern lithium-ion batteries typically have a life cycle of at least 10 years and more, so we’re yet to start seeing the bulk of used batteries that will require recycling or re-use. But it won’t be long before we do, so what do we do with them then?

One popular solution is to use them as power storage for domestic and commercial buildings. Back in 2018, Nissan launched the largest power storage facility in Europe to use both new and used car batteries; the Johann Cruijff ArenA in Amsterdam uses 63 second-hand EV battery packs and 85 new battery packs, which feed off of 4200 solar panels on the stadium roof.

This doesn’t mean that the stadium is ‘off grid’, although it is capable of powering the entire venue during an event for up to an hour (the equivalent of providing energy for 700,000 domestic homes) if necessary. Rather, Nissan’s battery-powered energy storage system acts as a generator that can back up the stadium’s energy supply during times of heavy power usage, reducing the strain on the grid at peak times.

Nissan also offers an off-the-shelf home or commercial energy storage unit called xStorage; a rival to Tesla’s Powerwall 2 system, although Nissan’s is different in that you can choose to have used or new EV batteries.

There’s an appealing circuitousness to the situation, if used electric car batteries can provide a home energy solution to solve the potential issue of increased car charging putting too much strain on the National Grid at peak times.

Even so, energy storage is far from a one-shot solution for the used EV battery issue. Some don’t think it’s a solution at all.

Transport applications require a highly energy dense battery to provide the necessary range from a comparably small battery. To achieve that small-but-powerful combination requires fairly large quantities of cobalt in lithium-ion batteries, but energy storage units in buildings don’t need to be so small and lightweight.

Cobalt production is a critical issue in battery production. Much of it is sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the mining process raises serious ethical and human rights concerns, so reducing dependency on it as demand for batteries rise is one of the greatest challenges.

Dr. Gavin Harper, a Faraday Institution Research Fellow at the Birmingham Energy Institute’s project on Recycling and Reuse of Lithium-ion batteries (ReLiB), stated that “some feel we should focus this precious resource of cobalt on more demanding applications such as EVs. It may make more economic sense to recycle EV batteries for use in brand new batteries for cars, rather than using them in a used state in a less demanding application [such as power storage].”

Mercedes-Benz would agree. The German manufacturer launched a home energy storage system using batteries from its range of EVs in April 2017, but the product was axed only a year later, with the company claiming that “it’s not necessary to have a car battery at home: They don’t move, they don’t freeze, it’s overdesigned.” So, for Mercedes-Benz at least, the costs didn’t add up.

Nissan, however, is adamant that EV battery tech is transferrable for home energy use. A spokesperson stated that Nissan “is committed to operating in the energy services market and is strongly placed to utilise both new and second life EV batteries for energy storage in a way that is commercially viable.”

Another significant consideration for EV batteries is the recycling process. Belgium-based company, Umicore, is one of the businesses already offering recycling for lithium-ion batteries. It reclaims the valuable metals using a combination of pyro-metallurgy and hydro-metallurgy, and while the company currently runs a pilot plant, it can still recycle around 35,000 EV batteries per year. According to a company spokesperson, Umicore “can easily scale up its recycling activities when the market grows, which we expect to happen in 2025.”

Even better - metals are infinitely recyclable, so they can be reclaimed from used batteries and used to produce new batteries that are as good as any other.

Tesla is open about its intentions to recycle its batteries, to the point where reclaimed metals from its used batteries would negate the need to mine new metals. Tesla CTO, JB Straubel, has stated that Tesla is “developing more processes on how to improve battery recycling to get more of the active materials back. Ultimately, what we want is a closed loop that reuses the same recycled materials.”

Another consideration is the changing battery tech. Renault-Nissan is working towards having a cobalt-free battery by 2025, which would change the value and environmental burden of its mass produced batteries significantly if the company achieves it.

Another big hope for the future is solid state batteries, which use a solid electrolyte (the chemical mixture that allows and regulates the flow of current), which promises to make the batteries safer and able to provide more energy than today’s li-ion batteries. Toyota and BMW are amongst the significant players who have stated a clear intent to be using solid state batteries in the near future. But what about the recyclability of these batteries?

According to Peter Slater, Professor of Materials Chemistry and Co-director of the Birmingham Centre for Energy Storage, the recyclability of solid state batteries “would present different challenges in terms of separating the components. In particular, it is likely that it would need chemical separation routes.”

Ultimately, if the appalling environmental implications of putting batteries into landfill weren’t persuasive enough, the other cold truth is that the metals and materials they contain are too valuable to waste.

So, while there may be many and varied answers to the question of ‘where will the used EV batteries go?’, ecological and economic good reason are (thankfully) unanimous on one thing: not into the ground.